History of Prisons

A Series of Reforms

Prison then, was meant to work as an alternative to these violent methods of punishment. Of course, this did not mean that prisons themselves were non-violent as they are, even today, heavily regulated, often with forms of police brutality. Further, there is the question of the inherent violence regarding the dehumanization and isolation of those residing within prisons.

Further, prisons were a direct extension of chattel slavery. After the abolition of slavery, there was a huge gap in the labour market that needed to be filled. Prison labour was then popularized as an alternative as prisoners were a free labour force. Many reccently freed slaves, with no jobs, and trying to function in a society that was still extremely racist, were criminalized, either wrongly, or for minor offenses that received a long sentence.Therefore, the slave trade quickly transformed into imprisonment, with people of colour, and previously freed slaves making up the majority of prison labourers.

Though seen as a positive alternative to slavery, the conditions were often much worse, as slaves were considered a white man’s property, and therefore, had some sense of protection, however small, whereas prison labour was both a way to fill a labour shortage as well as a punishment. They could be worked to death as there were always more “criminals” to fill their place. Even today, though conditions have changed, prison labourers that are paid still work at a significantly lower rate than minimum wage, and are exploited by the government and large corporations to produce for a fraction of the cost at the expense of those in the prison system as well as those in the job market at large. Similarly, the prison system, as a result of institutionalized racism, is still overwhelmingly occupied by people of colour. The prison system is an inherently racialized institution.

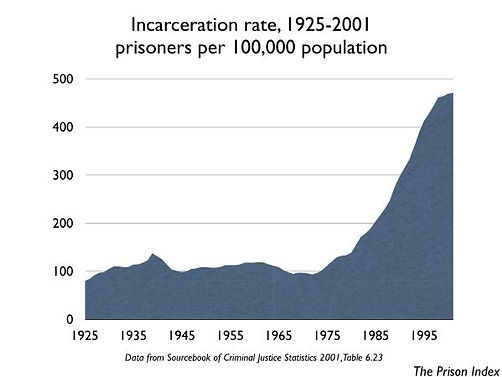

Jumping to the 1980’s, there was a drastic influx of prisons being built, in California, the number of prisons doubled in less than a decade (Davis, 2003). During this time, there was no dramatic increase in crime, but a growing awareness, and fear surrounding it. What purpose did these prisons serve then, if not in response to crime? Prisons have a lot to do with capitalism, and the rise of the prison industrial complex as we understand it now aligns with the rise of capitalism, that is, the need to profit off of marginalized peoples. We see this in the exponential growth of prisons on land that is otherwise undesirable, with the promise of jobs, economic growth, and the use of prison labour. However, we continually see that the economic stimulation promised for these areas does not occur.

Because of people’s fear towards crime, as taught by the media and our governments, we are so quick to accept that locking up a huge portion of the population is not only the only option that we are allowed, but in fact a smart, and morally just solution to protect ourselves. Indeed, movies and television shows about crime end almost formulaically, where the “bad guy” ends up in jail. This is the only form of justice that we seem to understand. Even in this very abbreviated history or prisons, it is clear that the system as it stands today is both extremely harmful, dependent on racist ideologies, and largely ineffective at actually preventing crimes from occuring. Throughout this website we hope to argue that “justice” does not come with imprisonment, or even punishment at all.

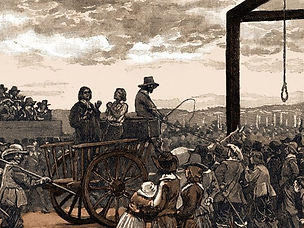

Prior to the American Revolution, America’s punishment system resembled that of England, which relied primarily on capital and corporal punishment. These types of punishments consisted of public displays of harm towards the person being punished (ex. beatings, whippings, hangings, killings). The importance of public attendance was crucial in this system of punishment, as it was designed to have the largest effect on the onlookers and not the individual. Public displays of corporal punishment were designed to seek revenge on the individual and to deter those who were watching from crime.

Reformers, such as John Howard and Benjamin Rush, proposed that English corporal and capital punishments did little to reform criminals, so they proposed that punishment be carried out in isolation so that the individual could be rehabilitated.

The idea of imprisonment was not new and even within this corporal/capital punishment system imprisonment was common, however, only in the case of a prisoner awaiting their public punishment. The penitentiary system, which saw imprisonment as punishment, only emerged around the time of the American Revolution. The penitentiary, and the imprisonment it provided, was regarded (by many, but not all), as rehabilitative.

Prison labourers surveyed by guard on horseback

Incarceration rates in federal prisons in the US have drastically increased