Where Are Prisons?

While prisons themselves may exist as one structural entity, there are many ways that police and prisons, and their focus on surveillance and punishment, emerge in a variety of structures that often go unnoticed.

Prisons, and their legacy of surveillance, control, and punishment emerge in the healthcare system in several ways.

Healthcare Systems

The first, and most obvious negative relationship between healthcare and policing is the frequency with which people with mental illness and disabilities are harmed by police.

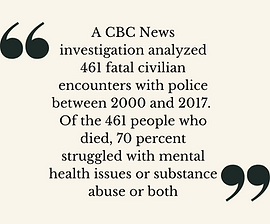

When mental illnesses, and the methods people use to cope with mental illnesses, are perceived as a threat they become punishable. A lack of adequate healthcare for people with mental illness and disabilities leads directly to these people being perceived by police officers as risks to the community. This police violence is amplified if the person is Black or Indigenous. Viewing mental health struggles as criminal allows police to react with force and violence, resulting, in many cases, in civilian fatalities.

There are few resources to respond to mental health crises within our current system that do not rely on policing and criminalization of the individual. Consequently, police are left to respond to calls dealing with mental health crises, despite their inadequate mental health training, implicit biases and - quite frankly - fear of disability. In saying that, it is not difficult to imagine alternatives to the police in these situations. Community based approaches to mental health, including de-escalation techniques performed by familiar faces, are much more effective at de-escalating mental health crises than the presence of police and the threat of criminalization.

The second negative relationship between healthcare and policing, is the frequency with which people with mental illness and disabilities are criminalized in the community.

The destruction of social safety nets, including social and healthcare services, economic and education availability, are directly related to the extent to which people with mental illnesses and disabilities are criminalized. The degree to which the criminalization of people with mental illnesses occur is correlated with other intersections of oppression such as race, gender, socio-economic status etc.

The irony here is that many prisons have facilities that provide healthcare to prisoners while they are imprisoned. This means that healthcare is unavailable to the general public, while it is available to inmates. This phenomenon results in people with mental health illnesses and disabilities receiving federal sentences under the assumption they will be able to receive treatment that is not available in the community.

Knowing this, it is easy to ask, “Why is it bad that prisons are providing necessary healthcare?”

To which we would counter, “Why is necessary healthcare not available to people before they are imprisoned?”

The issue with this is not the necessary services that prisons provide, it is viewing prisons as a solution to much wider social problems. Where community based mental health services and support are made available, prison healthcare is no longer needed. Abolition seeks to dismantle the notion that prisons are necessary in society, and this includes acknowledging the types of harm that are perpetuated when reformist policies seek to make the existing structure “better”. Adequate healthcare is necessary within prisons, however, prisons are not the solution to mental health issues.